Film Review: ‘The Royal Tailor

The clothes don't make the man, but they look gorgeous anyway in Lee Won-suk's intricately woven drama.

Maggie Lee

Chief Asia Film Critic

@maggiesama

Had Yves Saint Laurent met Jean Paul Gaultier during the Joseon dynasty, the ensuing costume drama might have looked something like “The Royal Tailor.” Dramatizing the rivalry between two sartorial masters — one a doyen of traditional elegance, the other an enfant terrible of design — director Lee Won-suk’s gorgeously styled and intricately woven yarn recalls the psychological twists of Mozart and Salieri in “Amadeus” in its engrossing tussles between craft and creativity, hard work and genius.

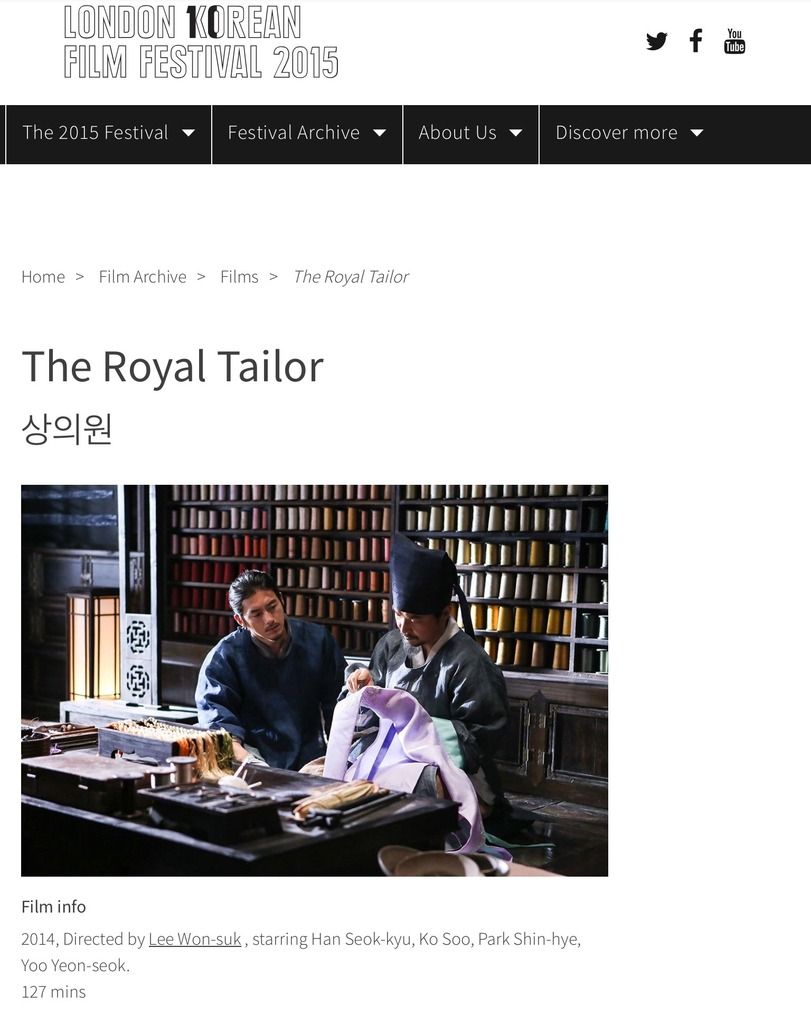

Arraying the actors in apparel that its protags would literally kill or die for, the pic merits repeat viewings with its sensational visual aesthetic alone, preferably on the big screen.

This isn’t the first Korean period drama to depict a commoner with a particular set of skills gaining intimate access to the royal circle, only to become a pawn in a web of murderous court intrigue. The genre was first popularized on TV by “Jewel in the Palace” and has found its way into theaters with such blockbusters as “King and the Clown” and “The Face Reader.”

Among these examples, “The Royal Tailor” stands out with its attention to technical details, conveying beauty in an especially tactile way.

The film is bookended by contempo scenes in a museum that exhibits the handiwork of Chul Dol-suk, a tailor who made a far-reaching impact on Korean fashion design. From there, it steps back in time to the Joseon dynasty, as the new king (Yoo Yeon-seok, “Hwayi”) summons Dol-suk (Han Suk-kyu, “The Berlin File,” “Swiri”), his father’s royal tailor, to make new clothes for every official attending his coronation. While Dol-suk throws himself into the task, relishing the prospect of being granted nobleman status for his labors, the queen’s maid accidentally burns the king’s old robe. When Dol-suk refuses to help for fear of breaking palace rules, Lee Kong-jin (Ko Soo, “The Front Line”), a young clothes-maker, is brought in as a last resort. Not only does he salvage the garment, he trims it into a better fit, earning a new assignment from the king: to furnish him with new hunting garb.

The light-hearted first half plays fast and loose with history, devising sights gags to send up Joseon fashion crimes like shoulder pads, push-up bras and platform shoes, which are amusingly anachronistic. But the scenes also serve to paint Kong-jin’s personality in vibrant strokes, such as his preference for the company of gisaeng (courtesans), who model his provocative designs with sexual confidence, to his habit of hobnobbing with high-ranking snobs.

Although Kong-jin is notorious for his womanizing ways, taking too much time “taking measurements” under virgins’ skirts, it’s love of the purest kind when he sets eyes on the queen (Park Shin-hye, in a total makeover from her modern look in “Cyrano Agency”), a breathtaking beauty rumored to be untouched by the king since their wedding night. When Kong-jin measures her waist with a skein of thread, the use of a lush closeup is more sensuous than any caress. To help her win the king’s affections, the tailor whips up a divine 15-layer gown so that she can gate-crash a state reception like Cinderella at the ball, and the episode sparkles with fairy-tale enchantment. Unfortunately, Kong-jin’s piece de resistance upstages menacing royal concubine So-yi (Lee Yoo-bi), whose gown was painstakingly designed by Dol-suk. In court, even the shortening of a sleeve or a new hairstyle can provoke deadly conspiracies.

While Dol-suk is the hands-on artisan who excels at embroidery, Kong-jin is the quintessential artist, experimenting with shapes and forms, and drawing inspiration from such mundance objects as a wine jar. His consciousness of style as an individualist statement is epitomized by his habit of burning his logo onto his costumes, the Joseon version of a fashion label. The rivalry between the two tailors is loaded with class implications; appalled by Kong-jin’s out-there designs, a nobleman proclaims, “A garment should reflect social status and rules,” echoing the law of the period that prescribes, legally, what each class can wear. While buttressing the hierarchical system, Dol-suk is ironically its victim, barred from donning any of the fancy clothes he makes.

As performances go, Ko gets by on good looks and rakish charm, letting Han do the heavy lifting. The Cary Grant of the Korean wave in the early 2000s, Han, who’s just hitting 51, has been making an uncertain transition as a character actor. Here he’s largely successful, revealing a dark, volatile nature and corrosive envy in subtle ways that invite pity, as well as respect for his dedication to his craft.

Ironically, Dol-suk’s complex about his lowly background parallels the king’s chip on his shoulder about being born of a palace maid and landing the throne by default. Lee Byoung-hak’s screenplay is particularly acerbic in rendering the king’s childhood hangups, which result in such unseemly behavior as bestowing his smelly socks on court officials as gifts, or comparing his queen to a piece of leftover barbecued short rib. Yoo convincingly limns his descent from mere pettiness to paranoia; his increasingly boorish gait suggests that, despite all his regalia, he lacks the qualities necessary in a ruler, reinforcing the film’s message that clothes do not make the man.

By contrast, the graceful Park emanates beauty from within.

Tech credits are excellent. The generic production design actually helps to spotlight Cho Sang-kyung’s resplendent costumes, which carefully reflect an evolution in taste to a style more akin to the hanbok, or Korean national costume, worn on formal occasions nowadays. Mowg’s score playfully mashes up ’70s jive with Western chamber music, while the crisp sound design accentuates the swish of skirts and rustle of taffeta. The Korean title “Sang-eui-won,” refers to the royal department of clothing founded in 1392.

Film Review: 'The Royal Tailor'

Reviewed at Vancouver Film Festival (Dragons & Tigers), Sept. 15, 2015. (Also in Busan Film Festival — Korean Cinema Today, Panorama.) Running time: 127 MIN. (Original title: "Sang-eui-won")